Known alternately as the coronavirus recession, the Great Shutdown, the Great Lockdown, or the Crisis of 2020, the breadth and depth of the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was swift and thorough. No sector will emerge unaffected, many individual businesses will not emerge at all.

Analysis from the World Bank’s June flagship report Global Prospects concludes that the “COVID-19 pandemic has, with alarming speed, delivered a global economic shock of enormous magnitude, leading to steep recessions in many countries. The baseline forecast envisions a 5.2 percent contraction in global GDP in 2020—the deepest global recession in eight decades, despite unprecedented policy support.”

This is a stark assessment. Seldom has such a destabilizing event had such a global and immediate impact on people and economies.

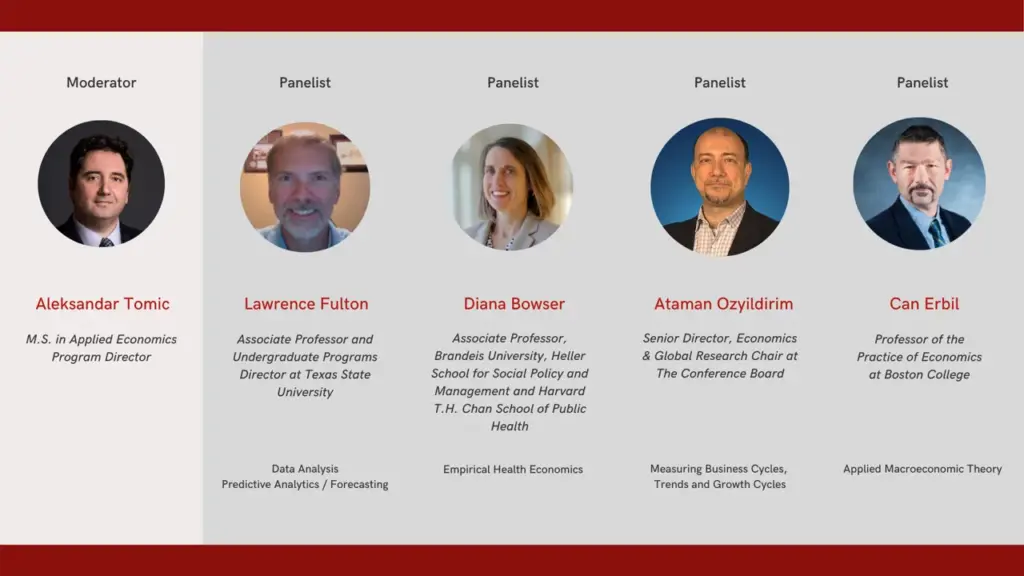

In May, Boston College’s Master of Science in Applied Economics program convened with four prominent economists and faculty members to discuss the global impact of the Great Shutdown. The panel discussed health economics, the complexities of modeling COVID-19 cases and hospital demand, and what the global economy may look like as we slowly emerge into a new normal.

The group reconvened in July to reflect on their previous projections and gauge the evolution of the pandemic since then. They consider what they got right, what they got wrong, and what the future may hold.

Moderating both conversations was Aleksandar Tomic, Ph.D. Dr. Tomic is Associate Dean for Strategy, Innovation, & Technology, and Program Director of the Master of Science in Applied Economics program at Boston College’s Woods College of Advancing Studies.

Following is a synopsis of these discussions.

Discussing the Economic Impact of an Outbreak

“To say that these are unprecedented times would be an understatement of at least a decade, if not a century,” said moderator Dr. Tomic at the start of the May 14 webinar. “We are dealing with a multidimensional issue.”

In order to “pull back the curtain on all things COVID,” Dr. Tomic was joined by four panelists. All four are faculty members of the Applied Economics Program at Boston College.

- Lawrence Fulton, Associate Professor and Undergraduate Programs Director, Texas State University.

- Diana Bowser, Associate Professor, Brandeis University, Heller School for Social Policy and Management and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

- Ataman Ozyildirim, Senior Director, Economics and Global Research Chair at The Conference Board.

- Can Erbil, Professor of the Practice of Economics at Boston College.

Let’s examine each of these experts’ takeaways, starting with their initial comments from the May webinar and then their follow up remarks from July.

Dr. Lawrence Fulton – Modeling and Data

Dr. Fulton teaches predictive analytics and machine learning. He spoke to the challenges of modeling COVID cases and projecting the course of the disease. “The hard part,” Dr. Fulton says, “is that this is a very, very new virus. And the data we have is suspect and limited.”

As more data comes in, models and forecasting improve, but Dr. Fulton cautions that “data may be poorly reported, incomplete, or just inaccurate. So, trying to use that for our own models is difficult at best. That becomes another issue with forecasting, and because COVID-19 is so new, we have very limited experience with it.”

Dr. Fulton praised the CDC’s use of “ensemble models,” including the Kermack-McKendrick theory devised in the early 20th century, to more sophisticated stochastics-based models. “I think that the CDC is doing a reasonable job at trying to get the forecast right, and given the forecast I’m looking at their curves, and it looks like by the middle of June we’ll definitely be at the flat spot, so a month from now we’ll definitely be at the flat spot.”

That forecast, of course, depended upon one of the most difficult things to model – human behavior. “If we can slow the contagion down through social distancing or other measures, if we can just slow it down, that allows us to get the resources into play so that there is not a mass casualty situation,” says Dr. Fulton.

When we rejoined with Dr. Fulton in July, he acknowledged that “we did have a little bit of a lull and now we have a resurgence.” Even with the loosening of restrictions, his emphasis going forward remains squarely on data and how we define our baseline assumptions and interpret data based on those assumptions. From the leadership down, failures in defining the forecasting problem has led to misleading conclusions. “There’s no forecasting,” he says. “When you start to change the variables you want to forecast, there’s no way you can do it accurately. Not only are we not recording a constant case rate, but we also are not reporting a common death rate. We are relying on bad data.”

Dr. Diana Bowser – Policies and Their Impact

Where Dr. Fulton spoke to data modeling and forecasting to better understand the virus’ trajectory, as a health economist, Dr. Diana Bowser studies health policy changes and their impact throughout the world. For Dr. Bowser, policy and the behavioral response to that policy is key.

“All countries are dealing with this COVID outbreak differently,” Dr. Bowser said in May. “I use that natural variation in those policies to understand the impact on health systems, and then eventually to measure how that impacts mortality and other outcomes in specific populations.” It is a process that usually takes years, but for this pandemic took only months.

“I think already we can make some of those associations,” Dr. Bowser said, “some countries that really came out early and put in strong public health and social distancing measures seem to be the ones that are containing the spread.” The result, she said, was “less impact on their health systems, which we measure in terms of the number of deaths per population size.”

Dr. Bowser pointed to Germany as one example. “Angela Merkel is a scientist,” she said, “she took this pandemic very seriously from the start.” Germany’s policy of aggressive testing, contact tracing, and public health rules that the population followed produced results. “The mortality rate there is quite low per 100,000.”

Other countries mentioned were the Czech Republic, where masks were mandatory staring March 21st, and New Zealand with its extremely low case and death rate. “they also have put in public policies that are easy to understand,” she said.

In July, Dr. Bowser confirmed her earlier observed associations between better outcomes and clear, consistent policies in place matched with adherence to those policies. The same countries mentioned in May maintained clear policy and messaging, the general population followed the guidelines set forth, and the results have been containment of the virus. Conversely countries like the U.K. and the U.S. with unclear and inconsistent messaging and resistance from large swaths of the population continue to suffer. “It’s going to get worse before it gets better,” she said of these countries.

While she feels that we still have “a lot to learn,” we’ve also “learned a lot” since May.

“We have learned a lot from our states and other countries. What I have learned is that responding to this pandemic, in theory, is not that hard. There are three things that countries need to do in an organized fashion. First, communication has to be clear. Secondly, testing and numbers are extremely important. The final piece is the context,” Dr. Bowser concluded.

Ataman Ozyildirim – An Alphabet Soup of Recovery

Many economists talk about the “alphabet soup” of recovery paths. When Dr. Ozyildirim spoke in May, the sharp contraction had already formed one side of the “V” symbolizing the economic plunge in response to the pandemic. The question at the time was “how is it going to recover on the other side?”

How the recovery unfolds, said Dr. Ozyildirim, depends on “when the peak hits and how long the stringent containment measures are kept in place.” The longer containment measures are kept in place the more likely the V-shaped recovering turns into a “U.” In other words a protracted bottom. But Dr. Ozyildirim sees a silver lining. “Many businesses around the world have responded by taking sort of very drastic measures,” he says.

However the economy finally recovers, business owners are thinking ahead to the new normal awaiting us as the world finally emerges from the health crisis. It is an opportunity to “reimagine” business life and commercial life. “We’re going to end up seeing much more innovation. So, in the longer run we might end up with a more positive trajectory for economies around the world.”

Two months on, with the resurgence of the virus in many parts of the U.S. and a see-saw of re-openings and re-closings, Dr. Ozyildirim emphasized uncertainty. Unlike other recessions, this one is driven by the health crisis and not from economic fundamentals. “The problem with the recession is that this is unique, and we have never seen it before. It is not based on business-cycle factors.”

“Now looking at the second half of the year, there is likely to be a demand shock because consumers’ sentiment and psychology are being affected. This starts a downward spiral, which in the end will dampen the recovery path.”

Can Erbil – A New Psychology for the New Normal

Dr. Erbil spoke in May about the fundamentals of demand. “It is the willingness and ability to pay,” he said, “and both of them are taking a hit.” The diminished ability for consumers to pay for goods and service is obvious. People are out of work, staying home, and unable to participate in the economy as they once had. Dr. Erbil brought attention to another, more pivotal long-term impact: the willingness to pay.

After two months of lockdown, “consumers are building new habits,” says Dr. Erbil. “They’ve had to think… time to reflect… that they have so many things. They’re starting to question; ‘do we really need this? Is this really necessary?’” This reflection from consumers is “going to really change the behavior of the economic agents,” he said.

There are changes on the supply side as well. Dr. Erbil pointed to restructuring supply chains, localization of production, and accelerating investment in automation technology. It is, Dr. Erbil explained, “a complete change in the supply behavior.” The buzzword he puts to this change is “de-desnsifying” the supply side economy.

In the end, Dr. Erbil’s follow up comments in July focused on the dangers of inequality. In the United States and around the world. “This is not just economic inequality,” he said, “we are also talking about racial inequality, opportunity inequality… it is really coming to the forefront”

With all this, the new habits, the new psychology, the systemic inequalities brought into stark focus from the events of the past few months, there is opportunity.

“This is something,” Dr. Erbil says, “this is an opportunity where we can actually make some adjustments in our new economy and maybe end up with a better place in the world.”